Double Bear Attack Survivor Interviewed at Shot Show

Arizona -(Ammoland.com)- Todd Orr is the survivor of a double mauling by a grizzly bear on 1 October, 2016. When the bear charged him, he used bear spray in an attempt to stop the attack. It did not work. Todd was taught that bear spray was superior to pistols for stopping charging bears. He took the use of bear spray seriously, kept an up to date can of spray in a holster, and had practiced quick drawing the spray and using it. He had used bear spray on a black bear twelve years previously.

In that instance he surprised the sleeping black bear from about 30 feet away. The bear came at him, and he was able to deploy bear spray from about 10 feet, directly into the bear's face. The bear instantly turned and ran off. He never saw that black bear again.

His frame of mind was that “Statistics from recorded bear attacks show that bear spray is more effective than a gun at stopping a bear charge.”

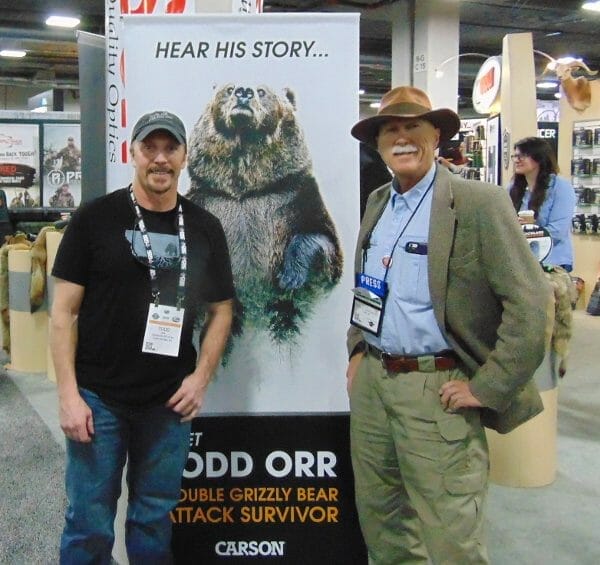

I met Todd at the 2018 shot show in Las Vegas. I was impressed. Todd appeared to have healed well. He is an outdoors professional, an obviously skilled woodsman and shooter. He is intelligent, thoughtful and articulate. He is an accomplished pistol shot, having harvested 28 elk with a pistol. He is a custom knife maker and has been an active reloader of his own ammunition for most of his life.

Todd was carrying a 10 mm Rock Island pistol with a six inch barrel and a 2×7 Burris variable handgun scope in a chest holster when he was attacked by the grizzly.

The 10 mm has shown itself to be a good bear stopper. The scope was in a custom mount made by Todd, that allows use of the open sights under the scope. Todd's 10 mm was being carried as a hunting gun, not as a defensive tool for bears.

It is axiomatic that under stress, people fall to the level of their training. This is exactly what Todd did. He carried bear spray with him as part of his job. He had attended a number of official bear identification and bear spray use classes over the years, as part of his work with the forest service. His work rules precluded the carry of a pistol. He had trained to quick draw the bear spray. Authorities higher in the organization had emphasized the effectiveness of bear spray.

Todd did as he was trained. He said he never thought of drawing the pistol to stop the attack.

Todd was seriously mauled. As he was self-evacuating, he was attacked again. He had a spare can of bear spray in his hand, but the surprise second attack offered no opportunity to use it. During the attack, his holster was ripped from his body, so he could not access his pistol.

Todd survived, recovered, and is getting on with his life. It could have been worse, or it could have been better.

Todd had been given bad information. Bear spray has *not* been shown to be more effective at stopping grizzly bear charges than guns. No such study has ever been conducted. The claims to that effect are junk science. I examined those claims in another article. They are made by people who compare two different studies with very different criteria for selection of the bear encounter incidents.

The firearms study involves incidents with aggressive bears where a high proportion of the incidents ended with people being injured. The authors have not released their data, but admit to a strong selection bias. That study is: Efficacy of firearms for bear deterrence in Alaska by Tom S. Smith, Stephen Herrero, and others, from 2012.There were only 269 incidents chosen. Many were during hunting situations where the bear was already wounded. From the study:

First, because bear-inflicted injuries are closely covered by the media, we likely did not miss many records where people were injured. Therefore, even if more incidents had been made available through the Alaska DLP database, we anticipate that these would have contributed few, if any, additional human injuries. Second, including more DLP records would have increased the number of bears killed by firearms. Finally, additional records would have likely improved firearm success rates from those reported here, but to what extent is unknown.

The strong selection bias was in favor of incidents where human injuries had occurred. A previous study with CHARACTERISTICS OF NONSPORT MORTALITIES TO BROWN AND BLACK BEARS AND HUMAN INJURIES FROM BEARS IN ALASKA, done in 1999, considered 2,000 incidents in Alaska where bears were killed in defense of life and property (the DLP records mentioned above). In that study, only two percent of the incidents resulted in injuries to humans. That study also has a selection bias, as only incidents in which the bear was killed are recorded in the database used.

The bear spray study compared to the firearms study was also done by Tom S. Smith, in 2008. The selection process for the incidents used was significantly different. Efficacy of Bear Deterrent Spray in Alaska examined 83 incidents with bears, humans, and bear spray. It is not clear how the incidents were chosen. Most involve incidents where the bear was merely curious or seeking food, but was not aggressive. From Dave Smith, a prominent author on how to avoid bear attacks:

Fact check: Efficacy of Bear Deterrent Spray in Alaska (2008) shows bear spray was 3 for 9 vs. charging grizzlies when people had time to use their spray. The study did not include data on incidents when people did not have time to use their spray or the “success” rate for bear spray would be lower.

Fifty of 72 incidents involved bears that were acting curious or seeking garbage or food before being sprayed. It is unethical and moronic to compare the results of the Alaska bear spray study to the results of the Alaska firearms study, which examined 269 carefully selected incidents involving gun use during “bear attacks.”

Using the tiny numbers found by Dave Smith, from the Bear Spray in Alaska study, the spray was only 33% effective in stopping charging grizzly bears. Such small numbers are not sufficient for good statistics, but they are what is available.

Comparing a study that deliberately selects incidents where people were injured (the Firearms study) to a study where Fifty of 72 incidents involved non-aggressive bears (the Bear Spray study) is junk science.

Bear spray has its uses. It is a valid option for people who are not comfortable with firearms or who do not wish to carry a firearm. It is better than nothing in places were firearms are prohibited or for people who are forbidden from carrying firearms.

A claim is often made that pistols are ineffective in stopping bear attacks. The best information we have is that pistols are very effective in stopping attacks. A number of hypothetical situations are often cited without any empirical evidence. Spray proponents claim pistols do not have enough power, are too difficult to use, or are not accurate enough.

I and associates found 28 incidents where handguns were used to defend against bear attacks. In only one of those incidents did use of the pistol fail to stop the attack. Sometimes people were injured before the pistol was used; that situation would be common to the use of both pistols and bear spray.

All of the incidents and links to the sources are detailed in this article. We have since found six more incidents that are being researched and evaluated. If included, they change the percentage of successful defenses very little. The inclusion of the newly found instances would only change the effectiveness from 96% to 97%.

The 96% effective rate compares favorably to the 84% effective rate for pistols in the 2012 Efficacy of Firearms study, previously cited. In that study, the authors report they included 37 instances of a handgun being present when a bear attacked a human. The instances collected were from 1883 to 2009. They recorded 6 failures to stop the attack out of the 37 instances. That is an 84% success rate. Pistol and ammunition technology have greatly improved since 1883.

Only four of the 28 incidents I and associates found, might have been included in the 37 instances that Smith reported in the Firearms study. None of the people in those four incidents were injured. The range of dates in the pistol bear defense article is from 1987 to 2017. They are heavily biased toward the present.

Using the criteria in Efficacy of Firearms study, of a handgun being present during a bear attack, Todd Orr's attack would have been counted as an instance of a handgun failure to stop the attack, even though there was no attempt to use the handgun during the attack.

In the article on the efficacy of bear spray, instances where bear spray was not used, even though present, were not counted. It is not clear if they were collected.

Todd Orr was a perfect candidate to successfully use a pistol to stop the attack by the grizzly that mauled him. He had ample opportunity to draw the pistol and prepare for the attack if he had not been trained to choose bear spray as the first, best, tool for the job.

Todd has since acquired a Smith & Wesson L frame model 69, stainless, five shot .44 magnum revolver. He carries both it and bear spray when feasible. It is handier and more powerful than his scope mounted 10 mm. More options are better. I hope Todd never has to use either option on another charging grizzly.

The .44 magnum revolver has been an effective stopper of grizzly bear attacks in the incidents we have collected. The combination did not fail in any of the 11 documented attacks where they were used as a defense against bears.

In collecting the pistol defense attacks, we included all attacks where a pistol was used or attempted to be used, to defend against a bear, that we could find. Todd's case is not included because he never attempted to use the pistol as a defensive tool.

©2018 by Dean Weingarten: Permission to share is granted when this notice is included.

About Dean Weingarten:

Dean Weingarten has been a peace officer, a military officer, was on the University of Wisconsin Pistol Team for four years, and was first certified to teach firearms safety in 1973. He taught the Arizona concealed carry course for fifteen years until the goal of constitutional carry was attained. He has degrees in meteorology and mining engineering, and recently retired from the Department of Defense after a 30 year career in Army Research, Development, Testing, and Evaluation.

No comments:

Post a Comment